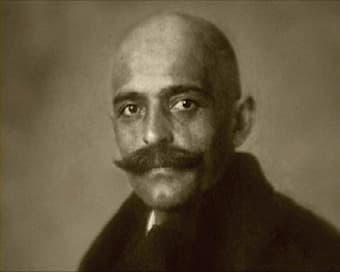

by Maureen Buja June 26th, 2022

The Ukrainian-born composer Thomas de Hartmann (1885-1956) studied at the Imperial Conservatory of Music with the three greatest Russian composers of the late 19th-century: Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov, Anton Arensky, and Sergei Taneyev after entering the conservatory at age 11. The first ballet of the 21-year-old composer impressed the Tsar enough to grant de Hartmann exemption from military duty. He took that opportunity to go to Munich to study conducting with Felix Mottl.

Munich in 1908 was a center for art creativity only matched at the time by Paris and Vienna. It was in Munich that he met Wassily Kandinsky, the two remaining friends until Kandinsky’s death in 1944.

Wassily Kandinsky

Just as Kandinsky was searching for the abstract in visual art, de Hartmann sought a visual parallel in music. Kandinsky introduced de Hartmann to the dancer Alexander Sacharoff which led to improvisation collaborations with ‘de Hartmann at the piano, Kandinsky shouting out dramatic scenarios based loosely on Russian folklore, and Sacharoff interpreting the music and storyline in dance’.

De Hartmann was called back to Russia with WWI to serve in his regiment. In 1916, de Hartmann met the man who would change his life, the Russian philosopher and mystic G.I. Gurdjieff. De Hartmann and his wife, the opera singer Olga de Schumacher, became part of Gurdjieff’s inner circle, remaining with him for the next 12 years.

Alexander Sacharoff

After 1917, when the de Hartmanns and Gurdjieff and others fled St. Petersburg, they ended up in Tiflis (Tbilisi) where de Hartmann joined Nicolas Tcherepnin, who was head of the conservatory. De Hartmann taught composition at the conservatory and was also appointed artistic head of the Tbilisi opera house. In 1920, the Gurdjieff / de Hartmann group went to Constantinople and then in 1922, just before civil war broke out in Turkey, they all went to Berlin and finally ended up in Paris where Gurdjieff founded his Institute for the Harmonious Development of Man in Fontainebleau.

In 1924, after a near-fatal car accident that laid Gurdjieff out for months and reduced the Institute’s income, de Hartmann started writing film music, under the name of Thomas Kross, eventually doing the music for some 50 films, most for Synchro-Ciné in Paris.

Thomas de Hartmann and his wife Olga in St Petersburg, 1906

After his recovery, Gurdjieff and de Hartmann collaborated on music together, in de Hartmann’s words: ‘Mr. Gurdjieff sometimes whistled or played on the piano with one finger a very complicated sort of melody-as are all Eastern melodies … to grasp these melodies and write them down in European notation, required a kind of tour de force and very often – probably to make the task more difficult for me – he would replay it a little differently’. These were published as the Sacred Music and used in the movement exercises practiced at the Institute. De Hartmann tells of the Institute’s trip to the US where, on the boat, the group practiced their exercises and Olga de Hartmann sang the Bell Song from Lakmé. Discipline was maintained when Gurdjieff yelled ‘Stop’, even though the boat was rolling so much that, as de Hartmann says, ‘at one point the piano slowly, but steadily, slid from one side of the stage to the other, myself following it on my stool’.

G.I. Gurdjieff

In 1929, Gurdjieff broke off relations with his oldest students, including the de Hartmanns, and they were forced to find a way to make a living, having lost all their wealth when they fled Russia. The reason for the break is unknown. Teaching brought in some money as did a stipend working for Belaieff Editions. De Hartmann found a new friend in the cellist Pablo Casals. They stayed in France during WWII where de Hartmann was able to complete several concertos, a symphony, and a cello sonata.

In 1950, the de Hartmanns moved to the US where he lectured and taught. One lecture in London brought him to the attention of Frank Lloyd Wright who invited them to Taliesen West in Arizona. Wright had married Olgivana Hinzenberg, another former pupil of Gurdjieff.

When we look at de Hartmann’s musical influences, we can start with Russian Romanticism of the late 19th century that he learned at conservatory, mix in the styles of Impressionism and Modernism that he was exposed to through Kandinsky, and then add in the early 20th-century Parisian influences of world music, jazz, bitonality, and then a bit of the ultra-romanticism of film music. He had a world of techniques at his fingertips and we see that in his orchestral music.

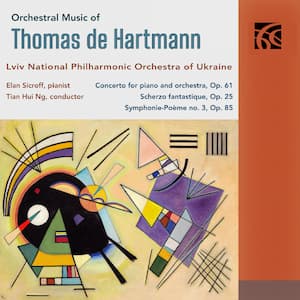

The opening movement of the Piano Concerto, Op. 61, written in 1939, grabs you immediately, and one writer then hears the orchestral response to the piano’s opening gesture as being more like John Williams’ Imperial March from Star Wars!

Thomas de Hartmann: Piano Concerto, Op. 61: I. — (Elan Sicroff, piano; Lviv National Philharmonic Symphony Orchestra; Tian Hui Ng, cond.)

https://interlude.nml3.naxosmusiclibrary.com/embedded/player/track?s=IK8544_001

As he would have learned writing film music, the concerto is episodic and continuous. The four movements should be played without a break, and movements end only with a fermata. Along with anticipating John Williams, the music has direct quotes from both George Gershwin and Scott Joplin, as well as music that brings both Rachmaninoff and Ravel to mind.

The recording also includes his Symphonie-Poème No. 3, Op. 85 of 1953. The three movements are based on Russian stories inspired by Russian writer Pavel Melnikov-Pechersky (1818-1883) and his 1874 novel V lesakh [In the Forests]. The first movement, Bolotnitsa (The Swamp Girl) is a story of a beautiful swamp girl who sits on a lily pad, asking all male passersby for help and promising mountains of gold and jewels in return – when they reach for her, she reaches for them and drags them down into the water. The second movement, Stroka (The Wicked Fly) is about a fly who chases the cattle until one falls in exhaustion… the fly then picks its next victim…

These two dark movements are balanced by the final movement, Radoniza (The Feast of Spring). We’re immediately in a solemn ritual and then a festive dance, all of which comes to an end when the sun rises. There’s hints of Stravinsky and Prokofiev in this spring ceremony.

The last piece on the recording is de Hartmann’s Scherzo fantastique, Op. 25. This was written in 1929, the year he parted ways with Gurdjieff. It is thought that the work may have been written for a film, as de Hartmann reserved the opus numbers between 23 and 45 in his catalogue for his film music, but this is the only work that he graced with an opus number. The ‘scherzo fantastique/fantasque’ genre is full of pieces with whole tone or chromatic scales; Rimsky-Korsakov also used octatonic scale to signal the fantastique. There are times when the work resembles Paul Dukas’ 1897 work The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, and, like that work, there seems to be a strong visual component.

Thomas de Hartmann: Scherzo-fantastique, Op. 25 (Elan Sicroff, piano; Lviv National Philharmonic Symphony Orchestra; Tian Hui Ng, cond.)

https://interlude.nml3.naxosmusiclibrary.com/embedded/player/work?s=9521112

Elan Sicroff

The pianist on the recording, Elan Sicroff, has been a particular advocate of the work of Thomas de Hartmann and G.I. Gurdjieff, recording both composer’s work. His association with the Gurdjieff community started when he attended International Academy for Continuous Education in Sherborne, UK, which was led by John G. Bennett, a leading exponent of Gurdjieff’s teachings. He also studied for 4 years with de Hartmann’s widow, Olga de Hartmann, who worked to have pianists understand the feeling in her husband’s writing. Sicroff started touring with de Hartmann’s work in 1982. It was at the urging of guitarist Robert Fripp that Sicroff started bringing de Hartmann’s classical music back to the concert halls. This recording is part of a planned multi-CD issue of de Hartmann’s solo piano, chamber and vocal works by The Thomas de Hartmann Project. To date 2 CDs of the piano music (NI 6409), 2 CDs of the chamber music (NI 6411) and a CD of the songs of de Hartmann (NI 6413) have been released.

The recording is a revelation about a composer who has the techniques and skills to write some of the finest 20th century music, but who has inexplicably fallen off most people’s listening lists. Take a listen to the music of Thomas de Hartmann and see how one Ukrainian composer manages to compress the sounds of so much of the 20th century into his work. As Robert Fripp noted, de Hartmann’s music is ‘as strangely inaudible as the composer is invisible…’. Some may know of him from his collaborations with Gurdjieff, but that is only a small percentage of what he created.